If there is an advantage to be had from being as old as the hills, it’s that I grew up at a time when there weren’t any helicopter moms. During spring holidays or summer breaks, I could get up in the morning, eat breakfast, and go out into the world with no questions asked. From the age of 12, I began to venture outside of my cloistered suburban neighborhood.

Some of my best memories are of the days when I would walk about a half mile from our house to catch a bus on Howard Street. If traffic was light, it took 20 minutes to get to the Howard Station. A few minutes after I boarded the Purple Line train, it would go underground. After a noisy, shaky 45-minute ride, I would get off at Adams and Wabash.

From there, it was a short walk to the Art Institute of Chicago. Usually, I stopped on the way at the nut vendor’s stall to purchase a quarter pound of freshly roasted cashews. That would be my sustenance until I reported home in time for supper.

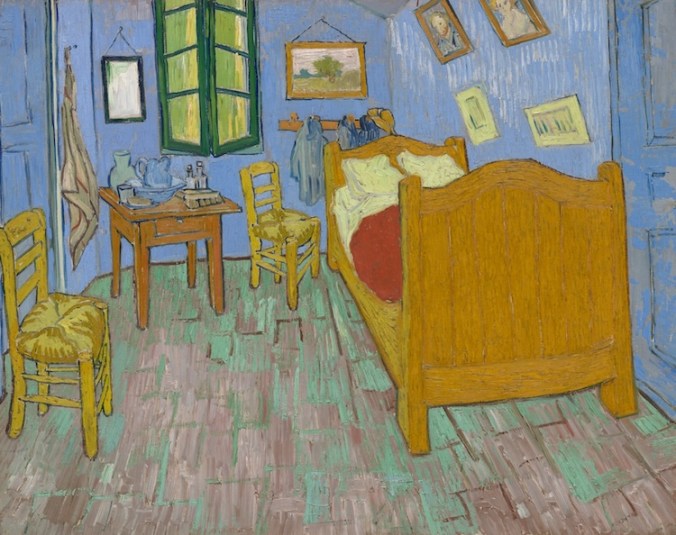

I had been visiting the Art Institute on field trips or with family for as long as I could remember. When I was a child, I particularly liked the French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. I was deeply in my comfort zone, when I stood in front of paintings like The Bedroom by Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890).

Decades later, one of Van Gogh’s darker, earlier works—The Potato Eaters—grabbed headlines, thanks to a foiled art heist. By the time this happened in April 1991, I was working as a designer and serving on the alumni council of California College of the Arts. The Potato Eaters became a huge topic of conversation after bumbling thieves grabbed it from the Vincent van Gogh National Museum in Amsterdam, along with about 20 other paintings. The unfortunate saga came to a screeching halt, when the getaway car blew a tire. Every painting was recovered within 35 minutes.

A priceless painting glorifying peasants eating potatoes might seem incongruous—until you learn that, a century earlier, the potato was controversial in Europe. In a strange way, van Gogh has a French pharmacist named Antoine-Augustin Parmentier (1737-1813) to thank for making it a fitting subject.

It may seem odd, but the parliament of the country that gave the world French fries had banned potatoes from 1748-1772, based on the belief that they were poisonous to humans. Parmentier was instrumental in getting the law overturned. During the Seven Years War, he stumbled into the realization that potatoes were nutritious.

While serving as a pharmacist in the French Army, Parmentier was captured by the Prussians. Throughout the duration of his imprisonment, he had to choose between eating potatoes or going hungry. Upon his return to France after the war, his research proved that potatoes were not toxic to people. Despite a declaration by the Paris Faculty of Medicine that potatoes were safe, the people of France were reluctant to accept the tubers as food fit for their consumption.

Parmentier went to dramatic lengths to make potatoes acceptable. He is said to have presented Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette with a bouquet of blue potato flowers. There are also stories of him inviting celebrities to banquets, where only potatoes were served. Benjamin Franklin, who was the American ambassador to France, is said to have been one of the guests.

King Louis granted Parmentier a large plot of land to use as a potato patch. As a public relations stunt, Parmentier hired armed guards to protect it, so that people would believe the plants were valuable. He secretly instructed the guards to accept even the smallest bribe they may be offered by anyone wanting to pilfer some seedlings, then look the other way while the theft occurred. Perhaps the ruse worked. Potato plants started sprouting all around the region.

The French Revolution slowed the progress of the popularization of the potato. Even so, a potato cookbook called La Cuisinière républicaine, qui enseigne la manière simple d’accomoder les pommes de terre ; avec quelques avis sur les soins nécessaires pour les conserver [Translation: The Republican Cook, which teaches the simple way to prepare potatoes; with some opinions on the care necessary to preserve them] by Madame Mérigot was published in 1794.

About the Artist

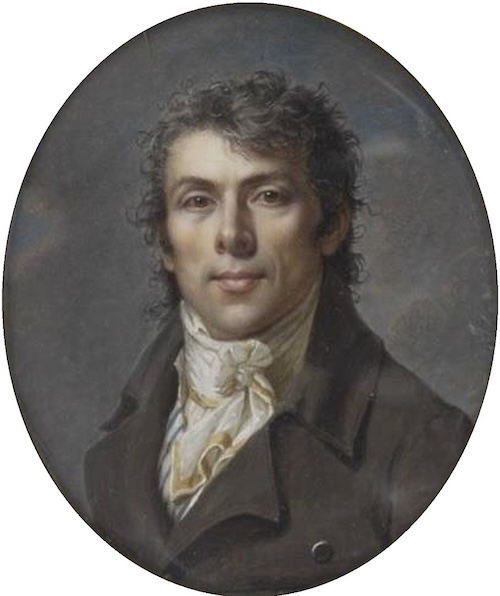

Antoine-Augustin Parmentier was one of many luminaries swirling around the 18th-century French court who sat for François Dumont (1751-1831), one of the greatest miniature artists of all time. The artist, born on January 7, 1751, in Lunéville, Kingdom of France, also painted the portraits of many members of the French royal family, including Queen Marie Antoinette.

François Dumont lived in Paris nearly all of his life, and he died there in 1831. His works are held in the Louvre and in the collection of the Pierpont Morgan Library.

Today, reflecting on Van Gogh’s works—I’m reminded how a humble tuber, championed through prison, pranks, and persistence, became immortalized in art.

Discover more from Art*Connections

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.