Queen Elizabeth II stood as a pillar against the endless stream of royal scandal. Although she presented herself as a stalwart role model, she couldn’t reliably steer her own children onto a noble path.

As much as we wish we could forget the screaming banner headlines in 1993 about Tampongate, it’s hard to purge the image from our heads. The carefree love talk between Charles, Prince of Wales, and his then-paramour Camilla, overheard by an unscrupulous electronic eavesdropper, was hardly titillating; it was simply embarrassing.

Then there was Sarah Ferguson. A year after her divorce from Andrew, Duke of York, she was shilling for Weight Watchers. In a 1997 commercial, she voiced over sultry poses and made us cringe, as she shared that she was once called the Duchess of Pork.

When it came to negative attention in the tabloids, Andrew surpassed his brother Charles. It may not be possible for him to ever entirely shake the stench of the Epstein cesspool.

The press fomented outrage at Charles for his adultery, while turning a blind eye to the extramarital shenanigans of his blonde, blue-eyed, fairy-tale wife. The daughter of the 8th Earl Spencer, Lady Diana Spencer, was perfectly cast for the part of princess and mother of future kings. But if we look through a clear lens, it’s obvious that the marriage between the 32-year-old Prince of Wales and the 20-year-old noblewoman was doomed from the start.

A little thing called the Royal Marriages Act of 1772 prevented Prince Charles from marrying Camilla Shand, the woman he loved. The Act required the Prince of Wales to have the reigning monarch’s approval for his choice of a bride. Camilla, whose father was landed gentry and whose mother was of minor noble birth, did not believe she would receive the Queen’s blessing. In 1973, while Charles was away on Navy duty, she married another suitor, Andrew Parker Bowles.

The Royal Marriages Act was the brainchild of King George III. He was 22-years-old in 1760, when he ascended to the throne to become King of Great Britain and Ireland.

George’s younger brother, Prince Henry, Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn, was a notorious lady’s man, involved in one compromising situation after another. In 1771, Henry fell in love with the widow Anne Horton and married her. King George disapproved. Hoping to prevent his descendants from putting passion before their obligations, he pushed Parliament to pass the Royal Marriages Act in response.

The Act didn’t have the dignifying effect that King George was going for. His oldest son and heir to the throne, George, Prince of Wales (later King George IV), secretly married Maria Fitzherbert, a Catholic widow.

The King’s favorite son and 2nd in line, Frederick, Duke of York, however, took his responsibilities to heart and married the Prussian Princess Royal.

But his third son, William, Duke of Clarence (later King William IV), moved Irish actress Dorothea Jordan and her four children into his home at Petersham Lodge in London. Eventually, they would have 10 children together.

Although George, Prince of Wales, loved Mrs. Fitzherbert, he eventually separated from her and married Caroline of Brunswick.

One thing the three Royal brothers had in common was their extravagance. Their enormous wealth couldn’t keep up with their shared penchant for gaming, horse racing, and decadence.

The public thirst for scandal is nothing new. Today’s social media memes and legacy newspaper headlines can be brutal. But the snarkiest images of our times have nothing on the caricatures produced in Georgian England. One of the most talented and biting artists back then was Isaac Cruikshank.

This print, dated June 19, 1795, is a copy of a print by Isaac Cruikshank made on May 25, 1795. Far from being an homage to the charitable instincts of the three eldest Royal brothers, it is a stinging commentary of how the recklessly debt-ridden Princes expected to be bailed out by their mistresses, wives, and the citizens of the Kingdom.

Prince William, in his blue Navy uniform, is holding one of his illegitimate children. He routinely overspends his allotment and takes his wife’s earnings from her successful theatre career. Next to him, the diminutive Frederica, Duchess of York clings to the arm of her Army officer husband, Frederick. She’s wondering what kind of world she entered into when she left Berlin and arrived in a place that lacked a grounding in values. Meanwhile her husband, the Duke, is thinking about hitting up his mistress for financial aid.

The Prince of Wales, in a blue coat and white breeches, faces his brothers. His new bride, Caroline, Princess of Wales, with three large plumes extending from her hat, stands behind him, staring over her shoulder, full of misgivings. The solid-looking Maria Fitzherbert faces Caroline, as she grips the financial settlement she received when she agreed to the separation.

Cruikshank didn’t let up. He drives the point home in a print dated July 12, 1795, showing the three Princes standing at the door to the House of Commons, begging cups in hand. (From left to right: Frederick, Duke of York; William, Duke of Clarence; George, Prince of Wales)

About the Artist

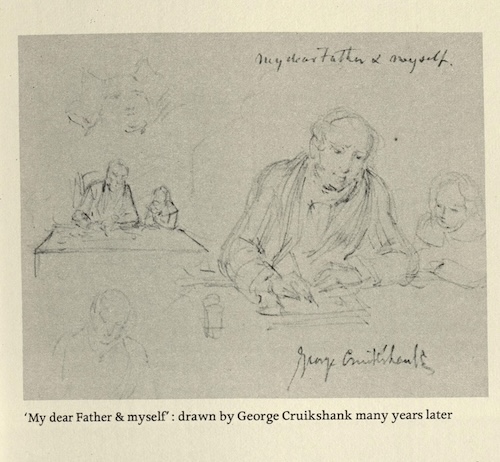

Isaac Cruikshank (1764-1811) was born October 5, 1764, in Edinburgh, Scotland. His sons Isaac Robert Cruikshank (1789–1856) and George Cruikshank (1792–1878) followed in his footsteps and became caricature artists. Isaac was one of the first to use speech balloons and narrative sequencing in his caricatures, putting him firmly in place as a pioneer in comic arts.

He died in London in April of 1811 at the age of 46 and was buried on April 16. His death is often attributed to alcohol poisoning from a legendary drinking contest.

Discover more from Art*Connections

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.