The truth hurts. The ugly truth. Your truth. My truth. Truth is messy. The whole truth and nothing but the truth. Yours truly. A grain of truth. True enough. Truth will out. The obvious truth. Tried and true. Gospel truth. Naked truth. True blue. Unvarnished truth. Ain’t it the truth? Or, in the immortal words of Benjamin Franklin, “Half the Truth is often a great Lie.” —from Poor Richard’s Almanack; July 1758.

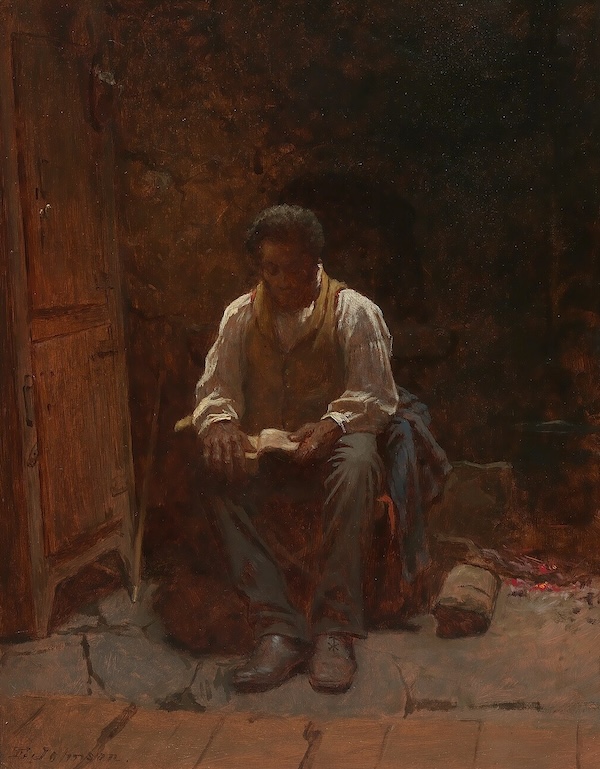

What got me thinking about the nature of truth was a painting by Eastman Johnson (1824-1906) called Negro Life at the South. Not long after it was exhibited in 1859 at the National Academy of Design in New York City, the painting came to be popularly called Old Kentucky Home. That was an odd renaming, since it depicts the life of African-American slaves on an urban street in Washington, D.C. This led me to do some further digging into what I thought I knew about the Civil War.

How many times have you been startled to find out that something you believed to be true was all a lie? Or maybe a shadow of truth had led to false conclusions? With the availability of news and information, it’s reasonable to expect this kind of misunderstanding to become rare. Instead we find a multitude of spokesmen, media outlets, pundits, and influencers who seek to shape our views rather than to illuminate the truth.

“How far such people may extend their influence—and what may be the consequences thereof is not easy to decide; but this we know, that it is not difficult by concealment of some facts, & the exaggeration of others, (where there is an influence) to bias a well-meaning mind—at least for a time—truth will ultimately prevail where pains is taken to bring it to light.” —George Washington to Charles Mynn Thruston, 10 August 1794

The distortion of facts to manipulate perception is not a new phenomenon. But in this information age, it can feel like we are bombarded with nonsense masquerading as reality.

“Well, most men have bound their eyes with one or another handkerchief, and attached themselves to some one of these communities of opinion. This conformity makes them not false in a few particulars, authors of a few lies, but false in all particulars. Their every truth is not quite true. Their two is not the real two, their four not the real four; so that every word they say chagrins us, and we know not where to begin to set them right. Meantime nature is not slow to equip us in the prison-uniform of the party to which we adhere.” —Ralph Waldo Emerson from The Essay on Self-Reliance; 1841

A few years ago, I had just settled into a vacation apartment in Cornwall with a view of Carbis Bay when, quite unexpectedly, I ended up in an argument with my traveling companion over the American Civil War.

I had made an observation about something in the news regarding the church in Virginia that both George Washington and Robert E. Lee had attended. This led to a passionate condemnation of Robert E. Lee, and a firm declaration that the North fought the evil South to abolish slavery. I stepped directly into the line of fire by suggesting that there had also been a clash in views on the Constitutional role of state sovereignty.

In my defense, I brought this up because I knew that Robert E. Lee was Abraham Lincoln’s first choice to lead the Union Army. President Lincoln was the good guy. He wouldn’t appoint Dr. Evil to a leadership position.

Despite General Lee’s ambivalence about slavery and secession, he turned down the President’s offer. His deep ties to the South and to his home state made him question the notion of taking up arms against his fellow Virginians.

In a letter to his sister Anne Lee Marshall, dated April 20, 1861, General Lee wrote, “With all my devotion to the Union and the feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home.”

Had tempers not flared, it is possible that my fellow sojourner and I might have found agreement on the key points. But maybe not. Truth may be absolute, but it is often nuanced. Maybe that fact alone would have been an irreconcilable point of contention.

As it turns out, we were both wrong in a way. Yes, the big push in the North for Abolition was behind the secession movement that begat the Confederacy. But President Lincoln’s primary motivation for sending the American army into battle against fellow citizens was not to abolish slavery. He did it to preserve the Union.

It only dawned on me when I saw Negro Life at the South that slave ownership had been legal in Washington D.C. Freedom came one year after the commencement of the Civil War, with the passage of the District of Columbia Emancipation Act of April 16, 1862.

When this legislation was enacted, it was still legal to own slaves in four Union border states: Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri. Neither an act of congress nor an executive order had the power to rectify that. If the states would not pass their own emancipation legislation, there would need to be a Constitutional amendment to get it done.

So when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Lincoln on January 1, 1863, it only freed the slaves in the Confederate states. Since they had seceded from the Union, the US Constitution was no longer a constraint on the President’s authority to act unilaterally. But of course, since the Southern states no longer considered themselves under U.S. jurisdiction, they did not comply with the order.

President Lincoln didn’t put pressure on the four border states to abolish slavery, because he feared they would secede from the Union and join the Confederacy. On November 1, 1864, Maryland passed a law ending slavery in that state. A new constitution enacted on February 11, 1865, ended enslavement in Missouri.

With the end of the American Civil War on May 26, 1865, and reunification of the nation, the federal proclamation against slavery in the Southern states could be enforced. Ironically, it was still legal for residents of Kentucky and Missouri to own slaves. It took the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution on December 6, 1865 to set them free.

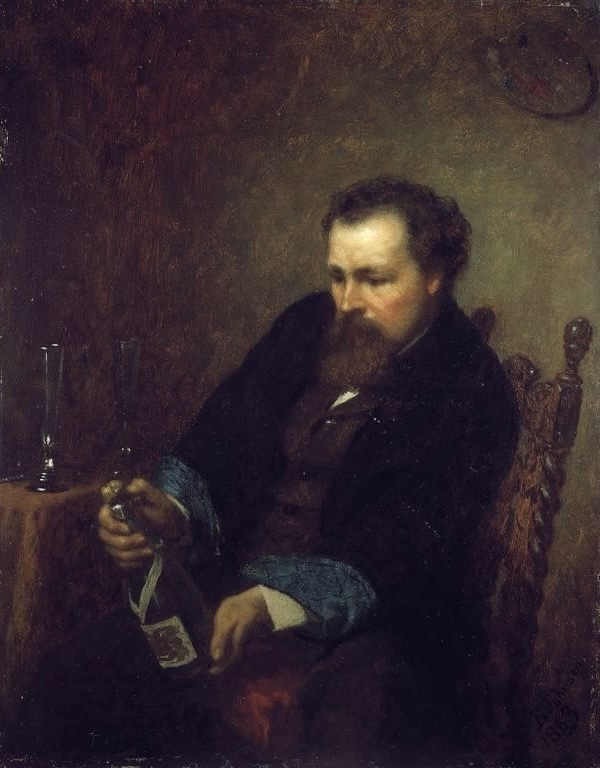

About the Artist: Eastman Johnson

Eastman Johnson (1824-1906) was born on July 29, 1824, in Lovell, Maine. He was one of the founders of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

When he was 16, he began his art career as an apprentice to a Boston lithographer. With his father’s appointment to a position in the administration of President James Polk, he moved with his family to Washington, D.C.

After traveling to Germany and The Hague to study painting, Mr. Johnson returned to the United States and stayed in Wisconsin for a while with his sister, before finally moving to New York City. He was a genre painter, whose paintings of Native Americans and African Americans were highly regarded for their realism.

Many prominent Americans sat for Mr. Johnson, including U.S. Presidents and literary figures.

On April 5, 1906, Eastman Johnson died in New York. He was 81-years old.

Discover more from Art*Connections

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.