In 1886, Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) was forced to resign his position as an instructor at the Philadelphia Academy of Art. At the time, it was unthinkable for a fully nude male to pose for female students in a life drawing class. While their male counterparts would be in a room with a naked guy, the women were sent to a separate room, to draw a male model whose private parts had been obscured by the prudent placement of a loincloth.

Maybe Mr. Eakins was just being helpful, but there were some complaints after he ushered a student named Amelia Van Buren into his studio and stripped naked. He did this on the pretext of illustrating the element of realism that was missing from her attempts to visualize a man’s pelvis.

The last straw came when he lifted a model’s loincloth in front of an entire class of full of women.

His only regret was that he had stayed at the Academy for as long as he did.

“I taught in the Academy from the opening of the schools until I was turned out, a period much longer than I should have permitted myself to remain there. My honors are misunderstanding, persecution and neglect, enhanced because unsought.” —From a letter to Harrison S. Morris, managing director of the Academy’s Museum and School operations, April 23, 1894

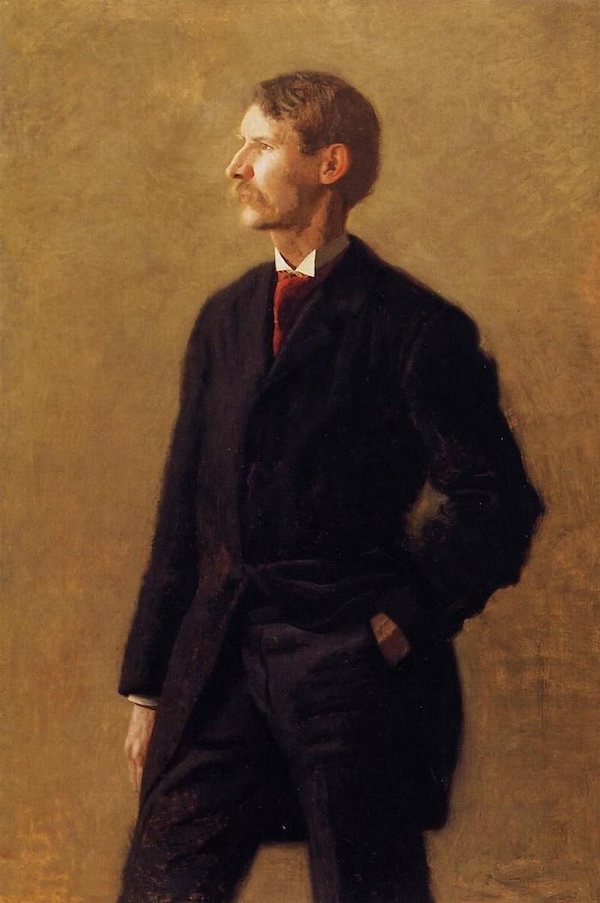

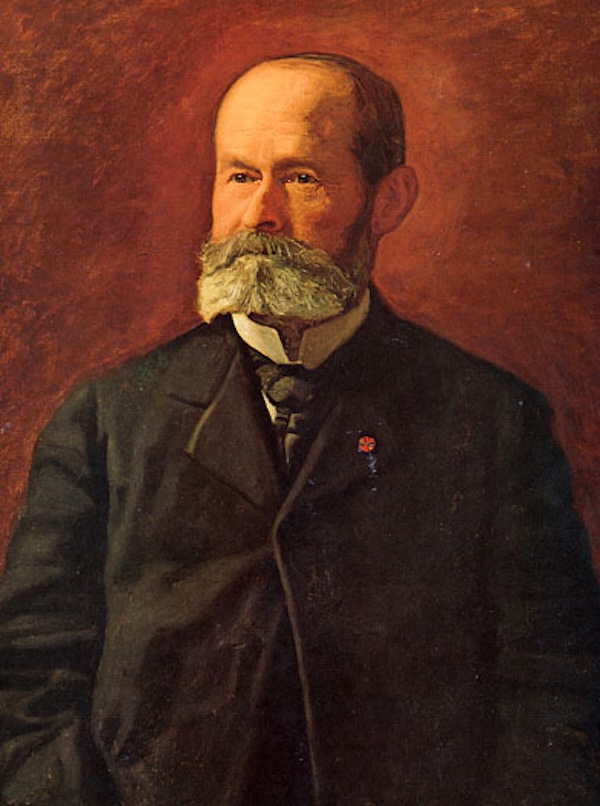

Although there are few paintings by Thomas Eakins that I would like to hang on my wall, I acknowledge that he occupies the top tier as a painter in the American Realism style. In my years as a master printer, gallery director, and curator, I learned that I didn’t have to like an art genre in order to recognize what worked.

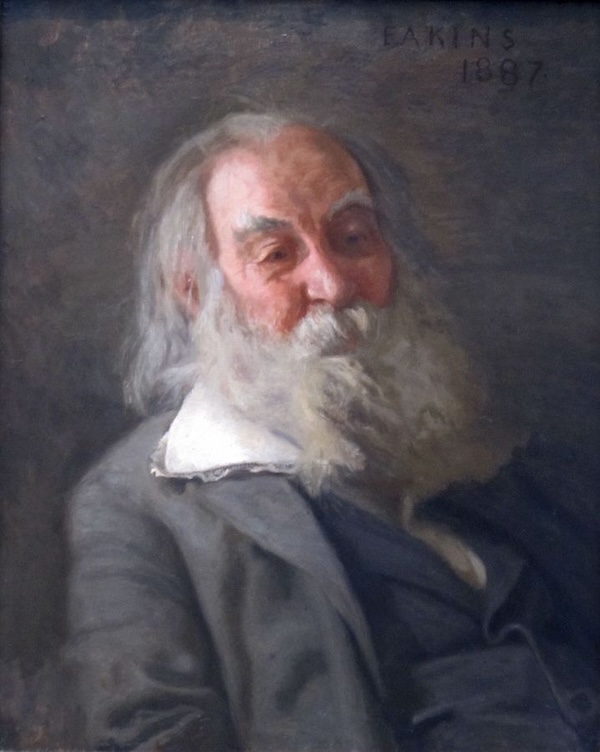

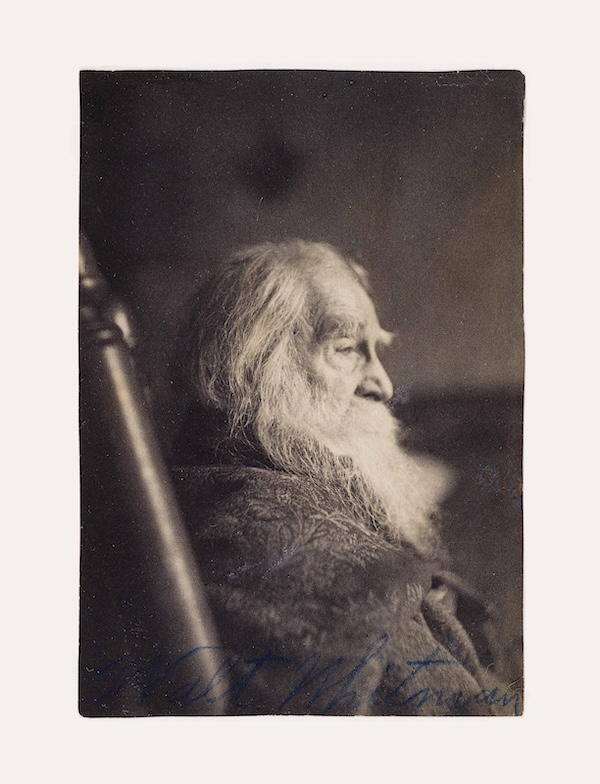

The Eakins portrait of poet Walt Whitman (1819-1892) is a masterpiece. It was painted in 1887, when the poet was unabashedly showing his age. The two men, who had become friends, had a lot in common in the way they perceived the world and represented it in the creative process.

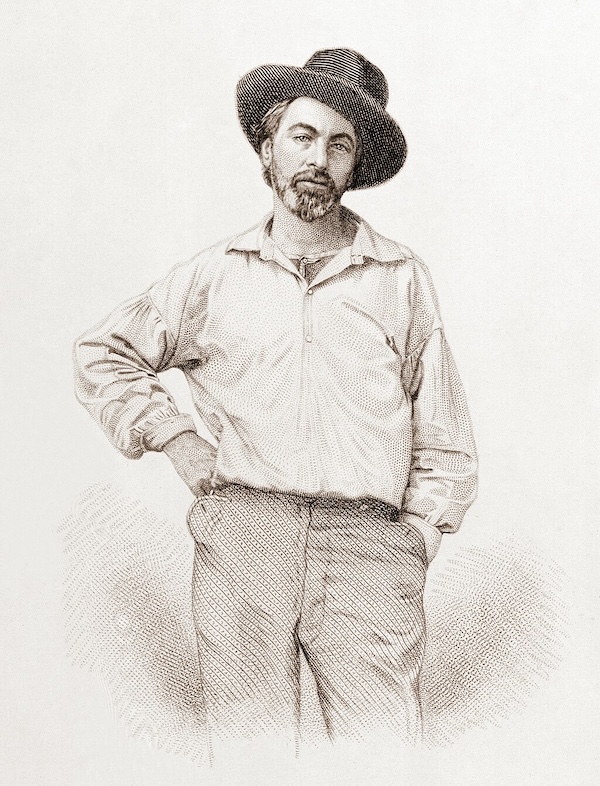

In 1855, Walt Whitman self-published a slim collection of his poetry entitled Leaves of Grass. The language and imagery were raw, compared to what was customary. Throughout his life, he would revise these poems and add more. In his second edition, published in 1856, he included some erotic poetry.

Mr. Whitman lost his job as a clerk with the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1865, after the Secretary of the Interior read Leaves of Grass and found it obscene. The sixth edition, published in Boston in 1881, was declared indecent by the Boston District Attorney and banned in that city in 1882. That same year, a Philadelphia publisher picked it up and released the seventh edition. It sold very well, thanks in part to the publicity out of Boston.

Leaves of Grass got another burst of publicity in 1998, with the release of the Starr Report, which revealed details of the improper relationship between US President Bill Clinton and a White House intern. One of the gifts from the President to his employee was a special edition of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Unlike the poet, the President retained his Federal job.

On May 31, 1891, the poet invited a group of friends to his home in Camden, New Jersey, to celebrate his 72nd birthday. Mr. Whitman led off with a toast to three great poets who had recently passed: William Cullen Bryant, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Then he saluted two other literary legends, who were still of this world: Alfred Lord Tennyson and John Greenleaf Whittier. Little could he have known that both of those giants would follow him in death in the next year.

After the opening remarks, Dr. D.G. Brinton toasted his host’s health.

“I thank you all, my friends. Don’t lay it on too thick,” Mr. Whitman admonished.

The friends went around the table, reading greetings and words of praise from well-wishers who could not be in attendance. Eventually, Mr. Whitman asked the people in the assembled group to express their own feelings or offer their reminiscences. Thomas Eakins was sitting there, but had remained silent.

And Eakins—what of Tom Eakins?” asked Mr. Whitman. “He is here. Haven’t you something to say to us, Eakins?”

“I am not a speaker,” Mr. Eakins replied.

“So much the better,” exclaimed Mr. Whitman. “You are more likely to say something.”

“Well, as some of you know,” Mr. Eakins began. “I some years ago—a few—painted a picture of Mr. Whitman. I began in the usual way, but soon found that the ordinary methods wouldn’t do,—that technique, rules and traditions would have to be thrown aside; that, before all else, he was to be treated as a man.”

About the Artist: Thomas Eakins

Thomas Eakins was born on July 25, 1844, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. A prolific painter and photographer, the impact of his Realist style was not fully appreciated during his lifetime.

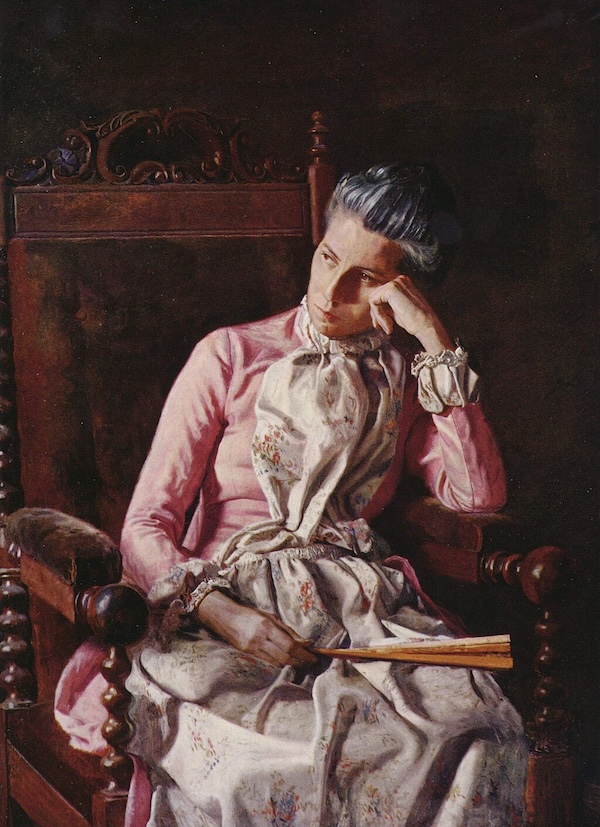

In 1884, Mr. Eakins married Susan Hannah Macdowell, who also became a painter and a photographer.

On June 25, 1916, Thomas Eakins died in Philiadelphia. He was 71.

Discover more from Art*Connections

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.