Even before the last brush strokes had been applied to the canvas, President Theodore Roosevelt was dissatisfied with his official White House portrait. Just the previous year, French artist Théobald Chartran (1849-1907) had painted a dignified yet casually posed portrait of First Lady Edith Roosevelt.

Since everyone was so impressed with the artist’s depiction of his wife, the President decided to sit for him as well. But now he was regretting it.

When the paint had dried, the portrait was packed off for a brief showing in France, where it was well received. But when it was returned to the White House, the President had it hung at the darkest spot on the wall of the upper corridor. Even so, his family chided him that in Chartran’s image, he looked weak. They nicknamed the portrait The Mewing Cat. Eventually the President had it destroyed.

Teddy Roosevelt wanted the world to know him by his tough-guy image. But Théobald Chartran had captured the rugged leader’s milder private persona.

Fortunately, the painting had been documented by the Société des Artistes Français, so at least we still have a monochrome image of it.

Early in 1903, John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) got to work on a new official portrait, and the President liked what he saw.

The skill and versatility of Théobald Chartran was reflected in the array of paintings he produced, ranging from the historical genre epitomized by his work entitled Signing of the Peace Protocol Between Spain and the United States, 12 August 1898, which is in the White House collection, to his portrayal of Maestro Arturo Toscanini at the Piano.

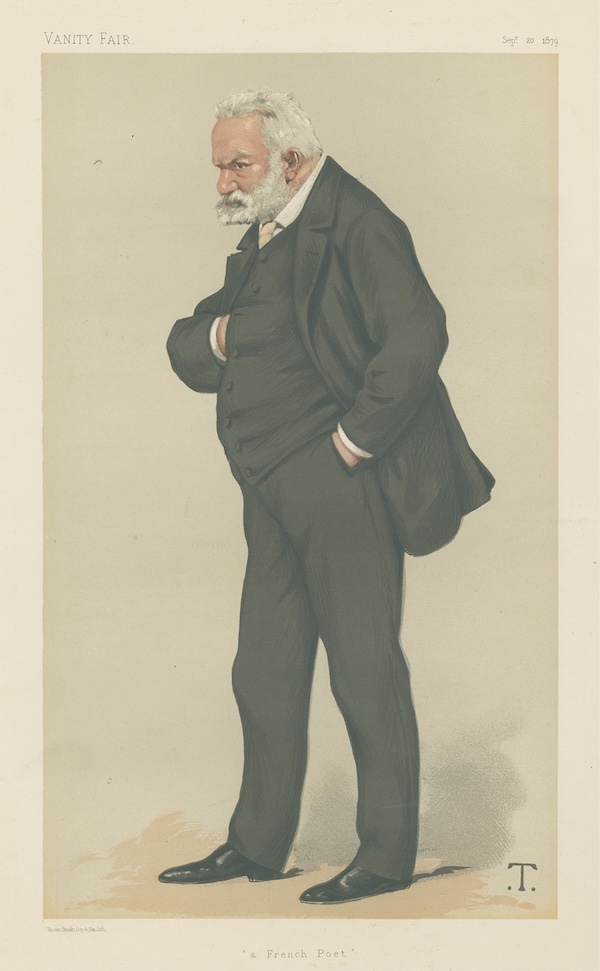

Beginning in 1878, using the pseudonym “T,” Mr. Chartran created numerous caricatures that adorned the covers of Vanity Fair. The National Portrait Gallery of London has over 80 of Chartran’s caricatures in its collection.

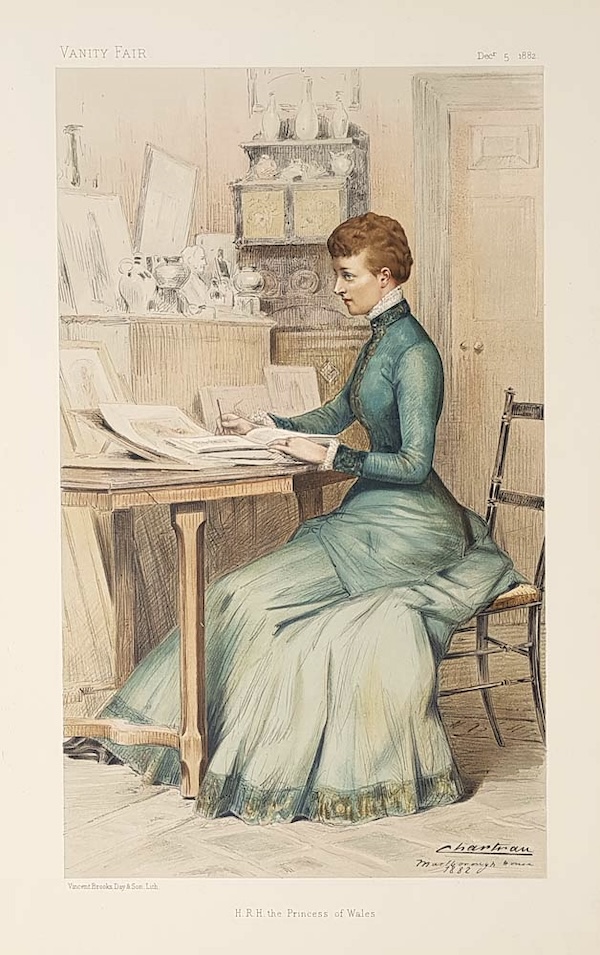

Occasionally the artist did portraits for the magazine under his true identity. On December 5, 1882, Vanity Fair published the chromolithograph of Her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales (Queen Alexandra) with the signature “Chartran.”

About the Artist: Théobald Chartran

Théobald Chartran was born in Besançon, France on July 20, 1849. His parents saw either a legal or military career in his future, but he had other ideas. He went to Paris, where he attended classes at the École des Beaux-Arts.

As his reputation grew, Mr. Chartran became one of the favorite artists among the elegant set.

In 1893, Théobald Chartran traveled to the United States. He continued to make annual trips to America until his death. He died in Paris on July 17, 1907.

Discover more from Art*Connections

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: The Legacy Continues | Roxane Gilbert