An embarrassment of riches was bequeathed to us from the paintbrushes of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), a founder and the first president of the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

© Royal Academy of Arts / Photographer: John Hammond

His portraits depict every luminary who lived, loved, fought, performed, wrote, ruled, and schemed during the reign of King George III. I came to know many of the people this master portrait artist depicted on canvas, as I researched and wrote my latest manuscript, a work of historical fiction set in the late 18th century.

One of the celebrities to sit for Sir Joshua was Georgiana Cavendish, née Spencer, Duchess of Devonshire (1757-1806). A fashion trendsetter and leading Whig hostess, she was the daughter of John Spencer, 1st Earl Spencer.

Georgiana’s colorful life has come under renewed scrutiny, because she is the fourth great aunt of Diana Spencer (1961-1997), the daughter of Charles Spencer, 9th Earl Spencer. Diana was the first wife of Charles, Prince of Wales, now King Charles III.

On Georgiana Spencer’s 17th birthday in 1774, she married William Cavendish, Duke of Devonshire. He was 25. The wedding between Charles, Prince of Wales, and Diana Spencer took place in 1981, about a month after her 20th birthday. The Prince was 32.

The emotional detachment of the Duke of Devonshire is usually blamed for Georgiana’s unhappiness in their marriage. And Charles, Prince of Wales (now Charles III), who had been in love with Camilla, his future queen, long before he and Diana tied the knot, is charged with causing the discord in the Royal union. But when are relationship dynamics cut and dried?

In the days of the internet’s infancy, the whirlwind affair between Diana and Dodi Fayed was streamed across tabloid headlines. The romantic storyline pushed by the press was that the recently divorced Princess of Wales and the Egyptian film producer had found true love. It was whispered that the couple had eked out a moment to look at wedding bands, sometime between disembarking from the yacht of Dodi’s billionaire dad in St. Tropez and the drunken driving collision in a Paris tunnel that claimed their lives.

By the time the dust settled and the conspiracy theories bubbled up, no one was mentioning that Diana and Dodi had only been an intimate couple for about two months. Was this really a love story writ large? Or would their passion have quickly consumed itself, if given the chance?

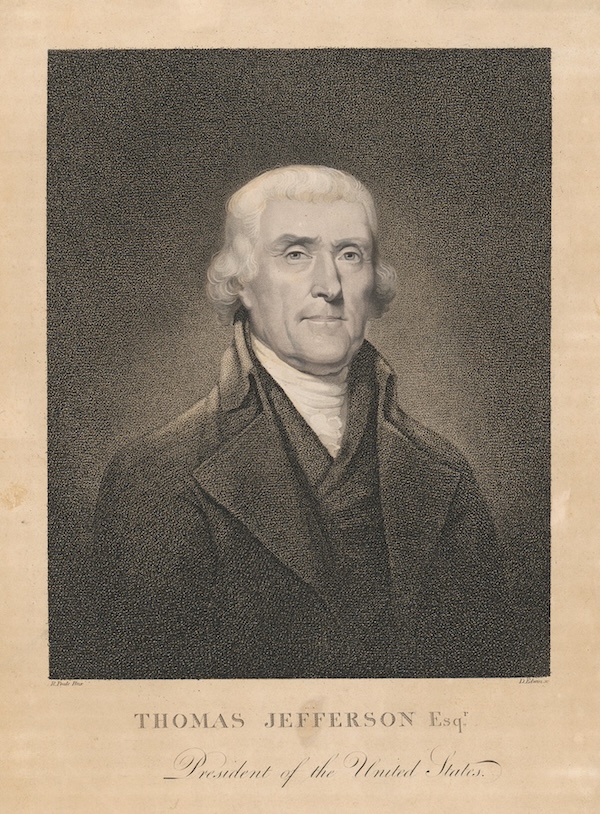

What do we really know? We learned about Diana’s great love affair from newspaper accounts. President Thomas Jefferson, a fierce defender of the right to a free press, wrote a letter to politician and author Barnabas Bidwell in 1806 and stated, “As for what is not true, you will always find abundance in the newspapers.”

The affair between Diana and Dodi may have been real enough. But true love? The kind of love you find in timeless fiction, like Romeo and Juliet?

There was talk that the dalliance of the Princess of Wales with the Egyptian playboy was payback to her former lover, a Pakistani heart specialist who had recently broken up with her. We may never know the underlying truth, but Diana’s legacy as a public-spirited, sympathetic figure was cemented by her shocking demise.

During her lifetime, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, was not entirely immune from mockery. Yet in light of her own scandalous behavior, her critics let her off easy. Her story is complicated, so I’ll give you a few highlights.

At the time Georgiana married the Duke of Devonshire in 1774, he had a pregnant mistress. He stayed in a relationship with his lover for a few years after their baby was born. Georgiana ended up raising the little girl, following the death of the child’s mother.

In 1782, Georgiana met Lady Elizabeth Foster, the daughter of the Earl of Bristol. She had recently left an unhappy marriage and was at loose ends. The two women quickly became best friends, and Georgiana invited Elizabeth to move in with her. It wasn’t long before Elizabeth also moved into the bedroom of Georgiana’s husband, the Duke of Devonshire. For some odd reason, this didn’t seem to bother Georgiana. The threesome lived together for nearly 25 years.

Another good friend of Georgiana was George, Prince of Wales. He desperately wanted her to be his lover, but she preferred to be his platonic confidante.

In the Georgian days, it was acceptable for married noblemen to have affairs. An aristocrat’s wife, however was only permitted this privilege after she had provided him with a male heir. Even then, the lady was required to be discreet.

It took Georgiana years of trying, but in 1790, she finally gave birth to the future Duke of Devonshire. By the next year, she was pregnant with the child of her lover, Charles Grey, the future Earl Grey and a rising star in the Whig Party. In 1830, Lord Grey became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

Charles Grey was handsome, but Georgiana’s passion for politics had played a large part in her attraction to him. The Duchess of Devonshire has been upheld by feminists as a groundbreaker for her political activism. Perhaps that is fair, but her practice of kissing strange men in exchange for votes brought her heaps of well-deserved ridicule.

Her hard-driving, party-hardy lifestyle took its toll. The Duchess drank as heavily as she lost at the gaming tables.

Poor Georgiana never saw her one-time lover rise to the pinnacle of British political power. She died in 1806 of liver disease at the age of 48. To the surprise of many, her cold, detached husband was distraught. Three years later, he married his long-time mistress Elizabeth Foster. Georgiana would probably have been pleased to see her best friend succeed her as Duchess of Devonshire.

About the Artist: Sir Joshua Reynolds

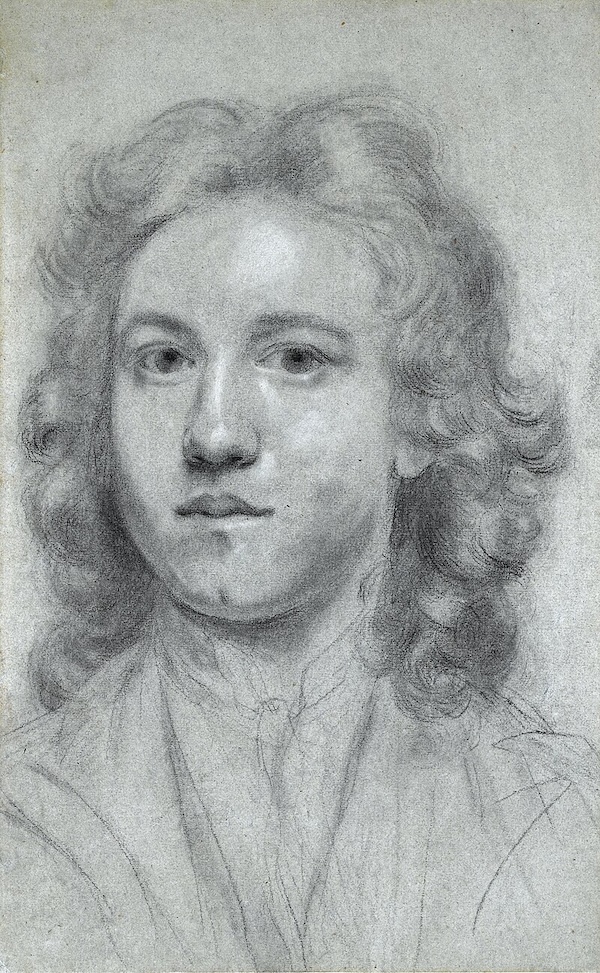

Sir Joshua Reynolds was born in the ancient village of Plympton in Devon, on July 16, 1723. He served as the town’s mayor in 1773, and his father was the headmaster of the Plympton Free Grammar School.

In 1740, Mr. Reynolds apprenticed to Devon-born artist Thomas Hudson, who was a portrait painter in London. Nine years later, he set out on a Mediterranean voyage, stopping in Lisbon and Algiers, and eventually arriving in Rome, where he spent two years. While there, he caught a bad cold that left him partially deaf.

Upon his return to London, Mr. Reynolds was in high demand as a portrait artist. In 1768, he became the first president of the Royal Academy of Arts, and he served in that position until the end of his life.

The following year, he was knighted by King George III.

A gregarious and intellectually curious man, Sir Joshua had many friends among London’s intelligentsia. This was illustrated in a stipple and line engraving titled A Literary Party at Sir Joshua’s Reynolds’s, published on October 1, 1851. The artwork featured the following sitters:

- Francis Barber (c.1745-1801); assistant to Samuel Johnson

- James Boswell (1740-1795); biographer of Samuel Johnson

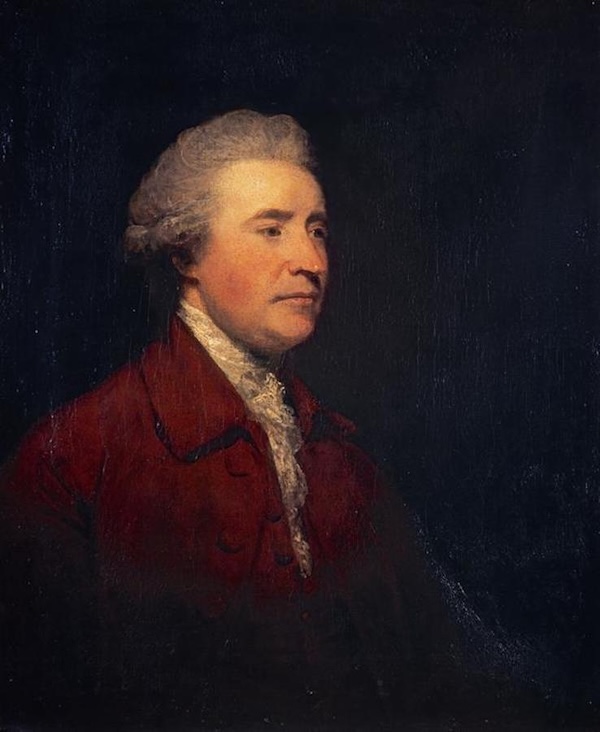

- Edmund Burke (1729-1797); statesman, political philosopher

- Charles Burney (1726-1814); musician and music historian

- David Garrick (1717-1779); playwright, actor, and theatre manager

- Oliver Goldsmith (1728-1774); writer

- Samuel Johnson (1709-1784); poet, essayist, and lexicographer

- Pasquale Paoli (1725-1807); Corsican general

- Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792); artist and president of the Royal Academy of Arts

- Thomas Warton the Younger (1728-1790); poet and literary historian

Sir Joshua was forced to retire in 1789, after losing his vision in his left eye. He became ill on New Year’s Day in 1792 and never recovered. After languishing for several weeks, he passed away on February 23.

Edmund Burke was with Sir Joshua on the night he died. The death of his friend moved him deeply.

That same night, Mr. Burke sat down and wrote a eulogy:

Sir Joshua Reynolds was on very many accounts one of the most memorable men of his Time. He was the first Englishman who added the praise of the elegant Arts to the other Glories of his Country. In Taste, in grace, in facility, in happy invention, and in the richness and Harmony of colouring, he was equal to the great masters of the renowned Ages….

He had too much merit not to excite some jealousy, too much innocence to provoke any enmity. The loss of no man of his time can be felt with more sincere, general, and unmixed sorrow. HAIL! AND FAREWELL!

If you enjoy art, history, and literature, please check out my other blog: roxanegilbert.com.

Discover more from Art*Connections

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.