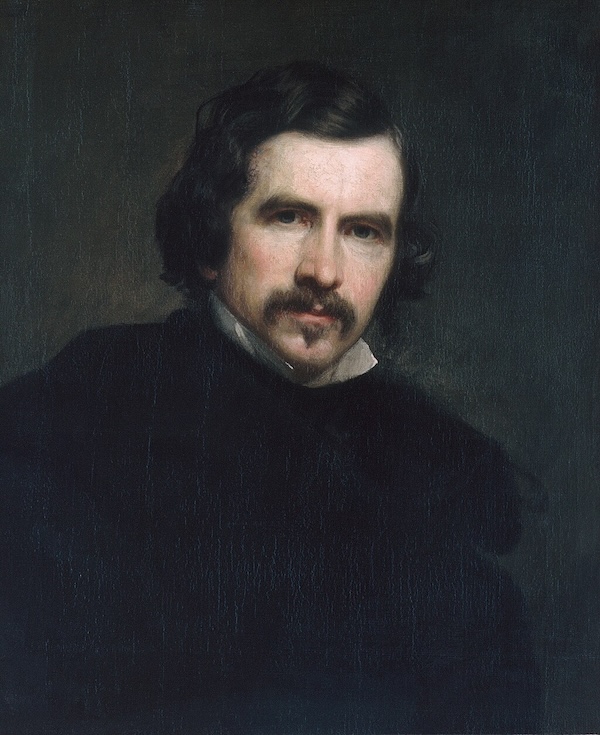

American artist George Peter Alexander Healy (1813-1894) left behind a vast body of work that is a historian’s dream.

He painted portraits of innumerable people of note, including William Tecumseh Sherman, Pope Pius IX, Daniel Webster, John Audubon, and Louis Philippe I, the Citizen King. The Corcoran Gallery in Washington DC commissioned Mr. Healy to paint the portraits of every US President from John Quincy Adams to Ulysses S. Grant. By my count, that’s a total of 13. It would be easy enough to dig up some historical gems from anyone in this extraordinary company.

But it is the untold stories that grab me. A portrait completed by Mr. Healy around 1881 of an elegant young woman named Miss Fanny Peabody sparked my curiosity. She is posed standing next to a piano. Her elbow is resting casually on top of an open music book, which is stacked upon some sheet music.

Born in Salem, Massachusetts in 1840, Fanny Peabody married 28-year-old William Powell Mason in 1863. He was a wealthy lawyer, who served as the director of several large companies in Boston.

It’s apparent from her portrait that Mrs. Mason loved music. Sometime in the winter of 1884-1885, she and her husband moved into their newly built home at 211 Commonwealth Avenue in the Back Bay neighborhood of Boston.

It wasn’t long before the Masons hired the renowned architect Arthur Rotch (1850-1894) to design a music room to be added onto the back of the house.

In 1891, German-Italian pianist and composer Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924) performed a recital in the newly completed music room. This was the first of what came to be called the Peabody Mason Concerts. Mrs. Mason died in 1895, but for many decades her daughter carried on the tradition of inviting world-class musicians to stage concerts at her homes in Massachusetts and Paris.

In addition to being a virtuoso pianist and composer, Maestro Busoni was an accomplished teacher. His best-known student was Kurt Weill (1900-1950), who wrote the music for the 1928 German musical play, The Three Penny Opera, with lyrics by Berthold Brecht (1898-1956). The top-selling recording from Mr. Weill’s most famous work was pop singer Bobby Darin’s rendition of Mack the Knife. You would be hard pressed to find a Baby Boomer who has never heard it.

After Maestro Busoni died in 1924, German-Expressionist painter and lithographer Willy Jaeckel (1888-1944) created an engraving of him.

Mr. Jaeckel had begun teaching at the University of the Arts in Berlin in 1922. In 1933, he became an associate professor. Nazi officials classified his artwork as degenerate in 1937, and Mr. Jaeckel was dismissed from the university. However, in response to student protests, he was soon reinstated.

The bombing raid of Berlin carried out by British twin-engined De Havilland Mosquitos on January 30, 1943, brought Willy Jaeckel’s life to an end.

About the Artist: George Peter Alexander Healy

George Peter Alexander Healy was born on July 15, 1813, in Boston, Massachusetts. He was the son of William Healy, an Irishman who fled Dublin after his family was financially ruined in the rebellion of 1798. Ending up in Boston, William married an American woman of English descent. Although he was born into poverty, George P.A. Healy decided at an early age that he was going to be an artist.

Mr. Healy had early success with his portraits. There were few opportunities to study art in Boston, so when he was 21, he booked passage on a ship bound for Paris. While the crew and passengers bided their time awaiting favorable sailing conditions, he paid a visit to Samuel Morse (1791-1872), remembered today as the inventor of Morse Code. However, as Mr. Healy knew, Samuel Morse had also been an artist.

In his autobiography Reminiscences of a Portrait Painter, published in 1894, Mr. Healy wrote that Professor Morse had tried to discourage him from becoming an artist.

Doubtless he did not remember his career as a painter with pleasure, for he said to me somewhat bitterly,—

“So you want to be an artist? You won’t make your salt — you won’t make your salt!”

“Then, sir,” answered I, “I must take my food without salt.”

Many of George P.A. Healy’s Presidential portraits are in the White House collection. His painting The Peacemakers depicts a strategy session held on March 27, 1865, aboard the steamer River Queen, involving President Abraham Lincoln, General Ulysses S. Grant, General William Tecumseh Sherman, and Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter during the final days of the American Civil War. President George H.W. Bush was so moved by it, that he had the painting displayed in his private office in the upstairs residence.

In the official White House portrait of President Bush, The Peacemakers is hanging on the wall behind him.

On January 7, 1990, in his Remarks Introducing the Presidential Lecture Series, President Bush emotionally described the impact The Peacemakers had on him.

In it you see the agony and the greatness of a man who nightly fell on his knees to ask the help of God. The painting shows two of his generals and an admiral meeting near the end of a war that pitted brother against brother. And outside at the moment a battle rages. And yet what we see in the distance is a rainbow – a symbol of hope, of the passing of the storm. The painting’s name: The Peacemakers. And for me, this is a constant reassurance that the cause of peace will triumph and that ours can be the future that Lincoln gave his life for: a future free of both tyranny and fear.

George P.A. Healy moved to Illinois in 1855, but he went to live in Europe in 1869. In 1892, at age 78, he returned to America to be near his family. He died in Chicago on June 24, 1894.

Discover more from Art*Connections

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.